The Chevelle Monologue:

This section of the website will detail the restoration progress of my 1967 Chevelle SS396 project. However, before I get started on that, I’d like to share a little bit about myself and how I became so interested in Chevelles.

The current Chevelle project is the fourth in a line of 1967 Chevelles I’ve owned so far, three if them being real 138 code SS396 cars. Before I get started into my latest project, I thought you might like to see some pictures and read a little bit about two of my previous Chevelles. Unfortunately I never took any pictures of my third Chevelle as I only owned it for a short time.

I’ll give you fair warning now…in case you hadn’t noticed from any of the other parts of the website, I like to write. A lot. I am a very detail-oriented person (which is definitely a plus being in the field of work I’m in), and if there is one thing I can’t stand, it’s when important details are left out solely for the sake of brevity.

So…go grab your favorite beverage, sit back and read along.

They say the choices of our adulthood are based on the experiences of our childhood.

That sounds plausible to me. Although today I am a certified Chevy nut, my first automotive allegiances weren’t necessarily towards the Chevrolet marque. My first lasting automotive impressions came around the formative age of eight years old, courtesy of a Limelight Yellow Dodge Charger which starred in the cult movie classic “Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry.”

I remember that night surprisingly well. My father had decided it would be a good night to take the family to the drive-in movies. He, my mother and I piled into our trusty 69 Plymouth Fury and headed out to our local drive-in movie theater, the “Melody 49 Drive-In.” Little did my father know that he was about to unwittingly introduce me to the world of hot rods!

I was still a bit too young to appreciate Peter Fonda’s “attitude”, much less Susan George’s curves, but I do remember thinking to myself that the little blue Chevy they were tooling around in at the beginning of the movie sounded kinda cool. Hey, even an 8-year-old kid can recognize a cool-sounding car when he hears one.

For the first part of the movie, the popcorn and sodapop I was busy scarfing down in the back seat was holding my focus more than the movie was.

Then the Charger made its appearance.

Y’know that “thing” a dog does when it hears something it’s never heard before?…that “ears-up, eyes wide-open, head tilted off to one side” thing? I vividly remember poking my head up over the back of that giant bench seat in similar fashion the minute Peter Fonda turned the Charger’s ignition key and that 440 engine rumbled to life.

That obnoxious green Dodge Charger was the coolest thing since sliced bread as far as I was concerned. Needless to say I was riveted to the screen for the rest of the movie. The seed had been planted.

Over the next few years, my obsession with cars grew even stronger. I begged my parents to buy me every issue of Hot Rod, Popular Hot Rodding and Car Craft (et al.) I saw on the news stands. By the time I was in my early teens, I probably had more than 100 car magazines at my disposal. While my buddies were busy swiping their fathers’ PLAYBOY magazines, I was learning about the inner-workings of the internal combustion engine from the pages of my favorite magazines.

Several makes and models of automobiles caught my eye over those years, but nothing had really made an impression like that Charger did. However, that was soon to change.

Fast-forward to around 1979:

It was around this time that I made the acquaintance of “Steve”, the resident neighborhood gear head. One day I was walking home from the local Stop-N-Go store, and as I passed an apartment complex where a friend lived, I saw someone working under the hood of a bright red `70 Camaro, complete with the obligatory 1970’s “stinkbug” stance (courtesy of maxed-out air shocks no doubt), Cragar mags and giant 50-series tires protruding from the rear quarter panels. Naturally, I had to go take a look.

Steve and I struck up a conversation, and we soon became good friends. He was well-versed in the automotive field, and shared a great deal of knowledge with me that would have taken years for me to learn otherwise. Steve mentioned to me on several occasions over the next year or so of another car he had besides the Camaro, a car he simply referred to as “the old blue Chevelle.” One day without notice he finally brought the Chevelle from his parents house to the apartment. The minute I laid eyes on it I fell in love with it. It was a “Charger moment” all over again, but the Chevelle had left a much deeper impression.

It was a Deepwater Blue 1967 Chevelle SS396 with a black bench seat interior and a 400 turbo transmission with a column shift. Steve informed me that the original 396 laid in hibernation on the garage floor at Steve’s parents house, and in it’s place was a rather stout (for the day) 355 small block Steve had just recently installed. Steve hopped in and fired it up for me. In that instant I was changed. Up until that moment, I had never actually experienced the audible and visual effects that a high compression engine with a giant camshaft had on the senses, I had only read about it in magazines. I stood there dumbfounded, listening with amazement to the wild cacophony of that 355 idling through open headers, and I took in the distinct aroma of spent high-test gasoline. My senses had officially been assaulted, and I was loving every moment of it.

Steve backed the Chevelle from its parking spot, feathering the throttle to keep the 355 from stalling out against the too-tight factory torque converter. He turned the car towards the alley beside his apartment and the Chevelle gradually began to roll forward. Suddenly and without warning, all hell broke loose. Steve mashed the throttle, and in a mili-second I was greeted by the insane scream of that 355 turning what had to be close to 8000 rpm. Two solid white pillars of tire smoke immediately engulfed the alley and the entire apartment complex as that Blue Chevelle wagged its tail all the way down the alley.

I just stood there with a silly ear-to-ear grin, covered with goosebumps. That was officially the coolest thing I had ever witnessed in my life up to that point. Still ranks up there pretty high today as well.

Steve made a hasty about-face at the end of the alley and pulled the Chevelle back into its place of mooring. You could barely see the end of the alley from the tire smoke that was still lingering in the air. My ears must have rang for a good half-hour after that, but I didn’t care. I’d just witnessed my first live demonstration of what a Musclecar was all about.

There are a few more stories relating to that Deepwater Blue Chevelle I could share, but lest I digress…

(Sadly, Steve sold that Chevelle a few years later. It quickly went through a couple more local owners, and tragically met it’s end one evening in a broadside accident at a 4-way intersection. I had purchased the original 396 from Steve a while before that, and the owner parted out the remains of the car and sent the rest to the crusher.)

That was it. I was hopelessly bent on the notion that I too would soon have my own `67 Chevelle. The search was on, and it didn’t take long before I found what I was looking for; the remains of a `67 Chevelle SS396 advertised in the local paper for a mere $200.00. I had just turned 16 when I purchased that `67 Chevelle in 1982. It was a true SS396 car, but had been liberated of its entire drivetrain and most of its interior by the time I got my hands on it. I drug it home and soon began my own `67 Chevelle journey.

The 396 from Steve’s Chevelle was given a basic rebuild (with the obligatory lumpy cam of course) and found its way between the fenders of my Chevelle. A junkyard 400 turbo transmission and Vega torque converter were bolted to the engine, and a 12 bolt rear end with 4.56 gears and a posi was scored from the local classified paper for $400.00. I had the car up and running again within a few months after buying it.

While the car was now capable of movement again under its own power, to say the car was “cosmetically challenged” would be a bit of an understatement. No, make that a colossal understatement. Frankly, the car looked like hell. It had what remained of a black enamel paint job on it when I purchased it, but it was in very poor condition. Since what little money I had went into getting the car running again, I did the only decent thing I could think of at the time; I covered the car in rattle-can black primer. As hard as this may be to believe, it was an improvement.

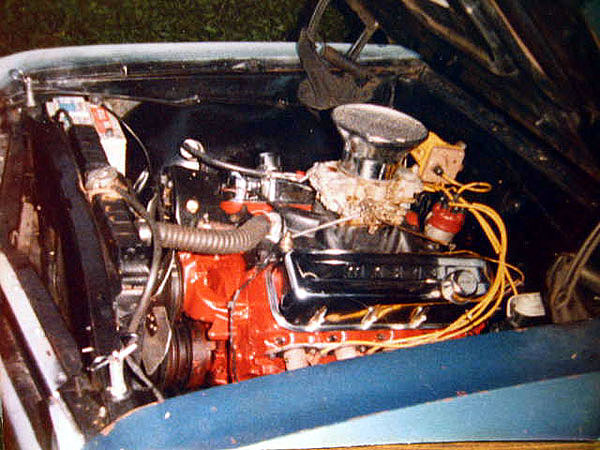

Below are two pics of precious few I still have of that car. Please bear in mind that these pics were taken with a Polaroid camera over 20 years ago, and time hasn’t been very kind to them. I cleaned them up as best I could. As I don’t have many pictures to work with, I can’t really put them in much of a chronological order.

The first pic is of the car sitting in the driveway after I’d just completed the installation an Edelbrock tunnel ram intake and a pair of Carter 750 cfm “competition series” carbs. This was a year or two after I’d gotten the car running

In the beginning…

My 2nd Chevelle: 11 second naturally aspirated pump gas street car in 1994

Tubbed with an 800+ HP 572 under the hood.

Again, the rattle can paint job was a definite improvement over what it looked like when I first drug it home, so take that for what it’s worth.

As soon as I’d finished installing the tunnel ram, much to my chagrin I discovered that my newly-purchased (junkyard) snorkle hood would not clear the intake and carbs as I had hoped, which explains the absence of the hood in the next picture. This was somewhere around the spring of 1984. At this point the car was equipped with the same 396 I had originally built (seen in it’s original incarnation on the next page), but now boasted forged 11-1 pistons, reconditioned rods with good rod bolts, and I swapped the oval port closed chamber heads from the original build for a set of rectangle port closed chamber heads. I had an original 163 intake and an 800 Holley on the car for a short time, but I don’t have any pictures of it in that state.

The square port head swap did basically what you would expect it to do; It killed off some low end torque (which wasn’t necessarily a bad thing considering the Kelley Springfield M50 tires I was running on the back at the time) in exchange for a very noticeable improvement in top-end power. Whereas the engine was pretty much done around 6500 rpm with the oval ports, the square ports let the engine pull much harder well over 7000 rpm. The addition of the tunnel ram furthered the same trend.

Above right is the 396 in its first incarnation in the Chevelle. At this point the engine was equipped with a stock steel crankshaft, factory rods and standard bore factory cast pistons. The cam was a second-hand Crane CC290-NC solid lifter stick I picked up from a local racer who’d stepped up to a bigger bumpstick in his car. The heads were stock 702 oval port closed chamber castings that I pocket-ported and had rebuilt with new guides, springs and a stock valve job. Yes, I was on the cheap then. $3.50 an hour at the local gas station didn’t provide many options when it came time to buy parts or machine work.

The intake was the stock cast iron Holley flanged unit that was installed from the factory on Steve’s Chevelle. I topped it with a rebuilt 700 cfm double pumper, but only after finding out that the throttle bores in the intake were too small and wouldn’t let the 700 open up completely. Another afternoon spent with a grinder took care of that issue. The ignition was handled by a Mallory Unilite distributor and an Accell SuperCoil. Of course, I had to top the mill with the obligatory (for the day, anyhow) Moroso chrome valve covers and Mr. Gasket velocity stack air cleaner. Doesn’t sound like much, does it? But for no more than what it was, it ran pretty well.

The above pic at the track lined up against a motorcycle is from the only outing to the drags I ever made with this car. The 396 was still in it’s first configuration, and the pass above was only my second pass ever down a dragstrip. The pass before this one resulted in a mid-14 second e.t. at only 90-something miles per hour. The miserable e.t was due to a severe lack of traction, and the low mph was due to the fact that I’d never been down a dragstrip before and didn’t know where the finish line was! I let off when I crossed the first stripe, which was the first mph line. My friend’s dad (who trailered me down there that day) showed me where the actual finish line was, and the second pass was notably more successful than the first one. I feathered the gas trying not to spin the tires as badly as I had the first time, but I still couldn’t get the car hooked until well into second gear. I no longer have the e.t. slip from this pass, but I remember it was a 13.2 at 107 miles per hour. Not too shabby all things considered. Yes, the bike whooped me. I did go for a third attempt, but misfortune struck as I wound up spinning a rod bearing in the burnout box which ended my first-ever outing at the drags. Even so, I still had one of the best times of my life that day.

In case you’re wondering where this pic was taken, it’s at Kil-Kare Dragway in Xenia, Ohio. The pic was taken somewhere during the summer of 1983. The 396 was pulled and rebuilt a second time to repair the damage done by the spun rod bearing. The second rebuild saw the addition of forged 11-1 pistons, reconditioned rods with good bolts, and a switch from oval port heads to rectangular port units and a factory aluminum dual plane intake. Unfortunately I never got the car back to the track in that configuration, but the performance improvement was pretty dramatic to say the least.

Re: the burnout pic: a friend had mentioned to me that he had some film in his camera he wanted to get developed, but there were still 2 or 3 unused shots on the roll he didn’t want to waste. As such, he asked me if I would entertain him with a quick burnout shot in front of his house so he could take a few pics. Being the good friend that I am, I naturally obliged.

It was around this time that the Chevelle’s aesthetics (perhaps stated more accurately, the Chevelle’s lack of aesthetics) finally started to get the best of me. It was ugly, but it was fast, and it was cool….but it was UGLY. Did I mention it was ugly?

So I started tearing the car apart with the intentions of rebuilding the suspension, and then to tackle the bodywork and paint. Big mistake on my part. What I failed to do was develop a PLAN before I began to tear the car apart, I just dove in head-first. It didn’t take very long at all to blow the car completely apart. However, getting it back together again became the insurmountable task. I quickly ran out of time, patience, and most importantly, money. It was then that I found myself forced to make the same decision countless other hot rodders have been forced to make over the years; it was time to get rid of it. I didn’t necessarily want to get rid of it, but I knew there was no way I would be able to come up with the necessary funds to do the car right in any reasonable amount of time.

So I sold the car. I still kick myself in the a** for doing that.

I thought I’d left myself an option to possibly get the car back someday by selling it to a good friend who was (at the time) in a much better position to finish the car than I was. A deal was struck where if he ever decided to sell the car, I would get first shot at buying it back. My friend got so far as to finish the front end rebuild and installed his own drivetrain in the car (mine was a bit more wild than he wanted). Any guesses as to what happened next?

Yep. He met a girl.

You can probably guess the rest, but in a nutshell, he soon decided that he wanted to get married, so he wanted to liquidate everything he had that was non-essential to raise funds for a down-payment on a house. Of course the Chevelle was the first thing to go up for sale. He told me his asking price, and remarkably enough I was in a position to buy the car back within a few weeks. Unfortunately he couldn’t wait that long and sold the car to someone else just days before I was to have the funds to buy it back.

This would normally be the end for most similar stories, but this story takes an interesting twist here.

Soon after I’d purchased the car, I lost the title for it. I had to get a new duplicate title issued for the car so I could get plates for it once I had it running. Several years after my friend sold the car, I stumbled upon the original title I’d lost many years before. Since I had the VIN at my disposal again, I decided to see if I could track the car down. I called the local licence bureau and was informed that they weren’t at liberty to divulge any information about the car. Figuring the pursuit a lost cause, I shelved the idea of locating the car again for several years. But in 2005 I decided to try once more as I had to call the DMV anyhow in regards to some other title issues.

Miracle of miracles, this time I struck pay dirt! I explained the situation to the exceptionally kind lady at the DMV, and at first she said she couldn’t tell me anything about the car due to privacy laws. I asked her if she could at least tell me if the car was still registered, and she said it was, and that it was still here in Ohio. Then she told me it was regsitered to a used car dealership. I asked her if she could tell me the name of the dealership who had the car now since it wasn’t technically a private party who owned it, and she said yes, she could.

You could’ve knocked me over with a feather at this point. A dream that had lasted nearly 20 years since I’d sold the car to my friend was on the verge of becoming a reality. She gave me the name of the business who owned the car, and I looked up their contact information on the internet. Taking as VERY deep breath, I placed the call.

The “used car salesman” (key term there, if you get my drift) who owned the car was, in the kindest of terms, less than encouraging. The bodywork had been “done” and the car was a “driver”, but I was told it had some pretty serious issues that still needed to be addressed. Then I inquired as to his asking price. I won’t repeat the figure, but suffice it to say that going solely by his verbal description of the car in its current state, he was clearly suffering from a severe case of “eBay-itis.”

Going WAY out on a limb, I asked him if he could send me a few pictures…just in case there might be any chance I would be willing to buy the car back for anything near his asking price. After reviewing the pictures he sent, I was forced to once again abandon my dream of once again owning my first Chevelle. I can only hope that whoever owns it today takes good care of it.

And so closes this chapter of my Chevelle saga.

Next up: Chevelle #2; “The race car with license plates”

Chevelle #2: The race car with license plates: “If you fail to plan, you plan to fail!”

Boy, did I ever screw this one up.

In 1991, I finally managed to locate and purchase another `67 Chevelle. This one was a base Malibu; originally a 327 Powerglide car, it now sported a 4-speed manual trans behind the warmed-over original 327. Bringing up the rear was a 12 bolt posi with 4.10 gears. Again, for no more than what it was, this was a fun car! Soon after I bought the car, I blew the Saginaw 4-speed that was in the car to smithereens. I found an early Muncie M20 box to take its place, and soon afterwards decided it was time to take it to the track.

Sporting a new pair of M&H cheater slicks, I un-corked the headers and headed for the water box. In the lane next to me was a `69 RoadRunner with a 383 Magnum and a 4-speed. We both did our burn-outs, staged, and when the tree came down, we launched dead-even out of the hole. We were side-by-side through first gear, but with each consecutive gear change that RoadRunner managed to inch ahead of me, eventually nudging past me by a fender in the lights. We both turned in mid 13 second elapsed times, his bettering mine by about a tenth of a second and one mile-per-hour. Talk about frustrating!

We pulled back into the staging lanes together after that run, and the driver of the RoadRunner struck up a conversation with me, complimenting me on the fact that he didn’t think that little small block would hang with him as well as it did. He and I wound up beside each other for three more passes. Each time the result was the same–he consistently got me by a fender in the lights. I quietly bolted the pipes back in place and drove home.

I goofed around with the 327 for a little while after that, but decided that if I really wanted to step it up, I wanted to go back to a big block again. A 454 core was procured, and the rebuild process began once again. I still had several parts left over from my original 396 from the first Chevelle since my friend didn’t want them when he bought the car from me. The 454 received its original steel crankshaft, a set of OEM 7/16″ dimple rods, and a set of original LS6 11-1 forged pistons that had come from a friends fathers race car. (As it turned out, my 454 core had next to no cylinder wall taper, which allowed it to go back together with standard bores)

The rectangle port heads were again freshened up, and this time they were equipped with a set of bigger springs to accommodate the Erson roller camshaft I had just ordered. The engine was buttoned up and topped with the same dual plane factory intake that once resided on my old 396, but this time a brand new Holley 850 cfm double pumper was placed on top.

I figured the Muncie wouldn’t be long for this world behind the 454, so I bought a 400 turbo trans and had it rebuilt with a B&M shift kit, and a B&M Holeshot torque converter was installed along with it. That torque converter wasn’t well suited for my engine, only stalling to around 2400 rpm. That was still more than enough to allow me to put the street tires I had on the car up in smoke at will, but really made the car soggy when the sticky M&H tires were on since the engine didn’t really start to come to life until about 4000 rpm.

Once the 454 was somewhat dialed in, I again drove the car to the track to see what it would do with the new 454 in place. Initial runs were relatively cautious, and resulted in a couple of mid-12 second elapsed times at around 107 mph. Subsequent tuning and an intake manifold swap to a Dart single plane eventually dropped the car into the 11.90’s at 113 mph, still in full street trim; a full 2 1/2″ crimp-bent exhaust system out to the rear bumper, my M&H cheater slicks, and a full tank of 93 octane pump gas.

I finally decided to change the exhaust to see what that would do for power output, so I bought a pair of 3 1/2″ Flowmaster 2-chamber race mufflers from a local street racer along with some 3 1/2″ down to 3″ reducers from JEGS, and headed to my local muffler shop. An hour later the 2 1/2 system was off and the 3 1/2″ system was on. I knew I’d made a change in the right direction as soon as I turned the key to back the car off of the lift. The engine didn’t just sound louder, it sounded completely different! A few quick whacks of the throttle on the way home confirmed my suspicions—this thing had woke up BIG-time!

And then my old pal Murphy reared his ugly head once again.

It was only a week or so after I’d had the bigger exhaust installed, and I was out cruising around with a friend. To note: the car was scheduled to go back to the track again that same week. The car was running better than it ever had. On the way home from getting lunch, I decided to lean into it a little bit. Just as the tach needle hit 7K in first gear, the engine let out a loud “POP”, and made a sound as if a muffler had fallen off. The engine died out, and as I glanced in the rear view mirror and saw a trail of heavy whitish-gray smoke behind me, I knew it wasn’t going to be pretty.

The postmortem revealed that the number 3 piston had disintegrated, taking out the cylinder wall with it. The head of the intake valve on #3 cylinder was missing as well, but I’m still not sure which one let go first…not that it really mattered at that point. Amazingly, nothing else was seriously damaged in the explosion, and I was actually able to save that block after having a sleeve installed in the #3 cylinder. However, the 454 didn’t make it back into that Chevelle, and lest I start to get ahead of myself…

It was around this time that the whole “Fastest Street Car” thing was starting to gain some attention. A friend and I went to the Memphis event in `92 and had an absolute blast. Naturally, I started to get the bright idea that I’d like to try my hand at that style of racing. Since the 454 was toast (I hadn’t fixed the block at that time yet), I thought to myself “what better time to start gathering parts to build something really serious?!?”

Silly me.

I again made the same mistake I’d made when I decided to tear my first Chevelle apart: I failed to plan. As a matter of fact, I made one of the cardinal sins of starting a new engine project; I started to build an engine based around a “good deal” I’d found on a used part instead of putting together a plan based around my goals and my abilities and starting from there. I made a second mistake as well, but I’ll get into that a little later. That good deal on a crank soon turned into a great deal on a virgin Mark IV Bowtie block, then a set of rods were purchased, then I had to order a set of custom pistons, and so on and so forth.

It took me a few years to finally save up enough money to buy all the parts I needed and to get that engine built. What I ended up with was a 572″ pump gas engine that eventually wound up making 730 ft.lbs of torque and roughly 800 horsepower just on the engine. That engine project taught me a LOT, and as such there was a “plus” side to it, but if I had the chance to do all over again, I would not do it…at least not like I did that time.

The second mistake I had made was the mistake of a lack of foresight; When I first started to gather parts to build this engine, the “rules” for the Fastest Street Car series were very well suited to what I had started to build. However, since it took me several years to complete the project, by the time the engine was done the rules had changed so much that my combination was obsolete before it had ever left the garage. I was now the proud owner of an 800 horsepower hunk of pump gas garage art.

My options were essentially limited to going street racing, going bracket racing, or driving the thing and enjoying it as best I could. Since I grew out of street racing long beforehand, that was out. Bracket racing had all the appeal of an ingrown toenail to me at the time, so that was out as well. That left one option–finish putting it together again and just drive it. So that’s just what I did.

The car eventually wound up getting back-halved since I determined that it was a cheaper alternative to fixing all the trunk and wheelhouse rust in the back of the car. Along with the back-half came an 8-point roll cage, a Dana 60 rear end with an Alston 4-link, and 30X13.5″ Mickey Thompson ET Street tires mounted on 15X10 Weld Draglite wheels.

I wound up driving the 572 on the street for about 4 years, just going to local cruise-ins and whatnot, but I never got the car back to the track with the 572 in it. To be honest, I really didn’t care what the car would run at that point. It was stupid-fast, and that was enough for me. Ultimately, several friends finally convinced me that I needed to take it to the track at least once to see what it could do. So I finally wrapped up the various loose ends so the car would pass tech (got the `cage certified, things like that) and picked a day to take the car to the track.

Enter Mr. Murphy.

My local track holds its test & tune sessions on Thursday evenings. On Wednesdays, there is a local car cruise that I had started to semi-regularly attend. I was on my way home from the cruise-in that fateful Wednesday night…the night before I had planned to take the car back to the track. I’d gotten about 2 blocks from the cruise-in and was approaching a stoplight when out of nowhere, the engine developed a severe miss-fire and started popping loudly through the exhaust. I immediately limped the car into a nearby gas station and shut the engine down. A quick peek under the hood revealed no obvious issues, so I fired it back up again just for a moment to see if I could figure out what went wrong. Again, there was nothing obvious, so I shut it down and called a friend who owned a tow truck to tow it back home for me. This was the first time since I’d owned the car that it made the trip home on a wrecker.

Once the car was back home safe & sound in my garage, I proceeded to start pulling things down to find out what the issue was. I pulled the plugs. Everything looked good, no issues there. Then I popped the valve covers off. A quick once-over revealed a LOT of slack in the #1 intake rocker arm. All the others checked out fine. So off came the intake & carb. The problem became apparent as soon as the intake was off. The roller lifter for #1 intake valve had gave up the ghost in rather gruesome fashion–the wheel was nowhere to be seen.

I thought to myself “OK, this isn’t so bad, I can pull it down to clean everything out, put in a new set of lifters and it’ll be good to go.”

Wrong.

Once I’d wrestled the remnants of the lifter body from the bore, a rather nasty gouge on the cam lobe was revealed. So much for a quick fix. I pulled the engine out and proceeded to tear it completely down. Then a somewhat more serious issue became apparent; When the body of the roller lifter broke, a piece of the lifter body managed to get wedged between a crank counterweight and the bottom of the wrist pin boss for the #1 piston. This left a very nasty gouge in the process, thus leaving said piston to spend the rest of its days as a rather expensive paperweight.

Did I mention that when I’d ordered my custom pistons several years before that no one advised me that it would be a good idea to order a couple of spares…just in case?

It wound up taking me almost 4 months to get replacement pistons made. And of course, I wound up having to order 4 pistons since they (who shall remain nameless) would not make only one piston for me. So I figured that while I was waiting on the pistons to arrive, I might as well send the heads (DART 360’s) out to DART and have them CNC ported.

To wrap up the 572 saga, after an all-too-long wait for my pistons to arrive, I finally got the engine buttoned back up and back in the car.

Enter one Mr. Murphy once again.

The engine didn’t have 20 minutes on it when disaster struck again. This time it was serious. I was checking the timing at about 3000 rpm when head of the #4 intake valve snapped off.

The subsequent tear-down revealed another wasted piston, a nice chip at the top of the #4 cylinder wall, and several thoroughly mangled combustion chambers courtesy of the shrapnel that managed to get pumped through the intake into several cylinders in the split-second between when the valve broke and the engine locked up. That was enough. Since there was no place to race the car with the big engine in it, and its only real purpose at that point was a street novelty, the decision was made to part the engine out and build something a little more civilized for the street. The block was bored another .030″ which cleaned up the boogered-up #4 cylinder wall and was sold. The heads were repaired & sold, as was the crankshaft and intake. Once the 572 had been parted out, the funds were used to start the build of a much milder, much more reliable 496 project.

This 496 was based on a 1973 vintage 454 2-bolt block, a SCAT 4340 crankshaft, the Manley 6.385 rods which were left over from the 572 engine, a set of 9-1 SRP pistons, Total Seal rings, a Crane solid lifter cam (the same grind being used in the current 496 in our `67 Chevelle project), a pair of AFR 315 c.c. CNC ported heads that I scored on eBay, a Dart intake and the ProSystems 1150 that was left over from the 572 build. Several other small items which were left over from the 572 were also employed on this engine, such as the still-perfect Cloyes timing set, the GM chrome timing cover, and the Manley head bolts.

The 496 installed and almost ready to come to life. During the time that the 572 was being parted out and the 496 was being assembled, I also tore the car down to a bare body & frame and detailed the undercarriage, rebuild the front suspension, and cleaned and detailed all of the underhood sheet metal and components. Please pardon the dusty fenders.

A change of priorities; Chevelle #2 finds a new home

The 496 was brought to life, and the rest of the loose ends on the car were wrapped up once again. However, by this time, the “novelty” of driving a tubbed car on the street had thoroughly worn off. I was tired of the log wagon ride, I was tired of climbing over a roll cage to get in & out of the car, and I was tired of wondering when I was going to get hassled again by the local constabulary just because it was a big-tired car. Considering what the whole “street car” thing has morphed into today, I had absolutely zero interest in ever pursuing that venue again, so I decided it was time to let someone else enjoy the car. In late 2005 I listed the car on eBay, but it didn’t meet the reserve. However, one of the perspective buyers contacted me after the auction had concluded, and a deal was struck. A few weeks later, the car was on a car hauler on its way to California to meet with its new owner.

Epilogue;

I remained in contact with the Chevelle’s new owner since he took delivery of the car. At my advice, he made a few small changes to the car to better work in conjunction with the 496; namely the 3.73 rear end gears (which was intended for the 572 on nitrous) were replaced with a set of 4.56 cogs, and the 1150 carburetor that was initially built for the 572 was replaced with a new ProSystems 1050 carburetor built specifically for the new 496. The torque converter that was custom-built for the 572 still needed to be changed out for one built for the new 496, but even so, the new owner has reported back to me that the car ran numerous 6.50’s at his local 1/8 mile track, and has trapped 112 mph in the process. 6.50’s in the 1/8 break down to 10.0’s in the 1/4. The 60′ times were only in the 1.40’s, so there was considerable room for improvement there still. With a little further refinement that was an easy 9 second pump gas combination that was about as fussy as an anvil.

The new owner ran the car in this configuration for a while, but as is all-too-often the case, the need for speed bug bit him hard. The 496 came back out and was prepped for use with a Vortech supercharger system. The cam was replaced with a COMP roller and the Dominator was swapped for a blow through 4150 style unit. The ignition and fuel systems were upgraded as necessary, and the car wound up running 5.50’s @ 130+ in the 1/8 mile, which breaks down to roughly mid 8’s @ 155+ in the 1/4 mile. If you visit the Vortech Superchargers website, you’ll see pics and a blurb of the car in their customer’s cars section.

And so concludes the saga of my first two Chevelles. As I mentioned earlier I’ve owned 4 in total, but I never got any pictures of the third car. Since I only owned that car for a short time, there’s really not too much to tell about it.

Which brings me to my current Chevelle project. This time, things are going to be a LOT different.

Needless to say, I’ve learned from my mistakes, and I have absolutely no intention of ever repeating them again. This time around, I developed a plan for the car before I ever even purchased it. There will be no more “race” parts to be contended with in a true street environment. There will be no narrowed rear ends, no roll cages, nothing even remotely “exotic” will find its way on this car. The plan for this car is actually quite simple:

The car will be completely restored, but not to the point of adding all the correct chalk marks and paint daubs…just a very nice #2 style restoration. However, since the original 396 engine, 4-speed transmission, and 12 bolt rear end for this car have long since been lost, I am taking certain “liberties” with the car:

Instead of installing an original-style oval port 396, the car will receive a “slightly modified” big block dressed out to essentially resemble an L78 (or LS6) style engine. A Muncie 4-speed will once again take up residence inside the transmission tunnel, but this one will be based around an aftermarket case for a little more durability during “spirited” driving. Finally, a 12 bolt rear will once again reside under the stern of the car, but this one is equipped with a 4.56 gear set…”just for fun.”

So without further ado, allow me to introduce you to my current, and hopefully final `67 Chevelle SS396 project.

As soon as the “race car with a license plate” Chevelle was gone, the search began for a suitable replacement. Surprisingly, my search didn’t take as long as I’d expected it to. I soon found what I deemed to be a suitable candidate advertised on a classic car dealers website. For reasons which will be obvious shortly, the name of the dealer will not be disclosed here.

I placed a call to the dealer and spoke to a salesman about the car they had advertised on their website. I was told it was a “100{e8a31ad70eb76b9d1736af28c4c10c5ce60babf18dd7728d2fa05ac44ba5f2cd} rust free” car that had a “rebuilt engine” in it, and that it was in fact a legitimate “138 code” SS car. I took the time to do some internet research on the dealership, and for the most part, what I read was positive and encouraging. As such, a price was negotiated and I placed a deposit on the car. (Note: I was assured I would receive the car exactly as it was pictured below)

That’s another mistake I’ll never make again.

At any rate, here are the pics of the car just as they were posted on the dealer website. (please note what’s residing in the engine bay)

Here’s where things get interesting. Once the final shipping arrangements had finally been ironed out, the dealer emailed me an “invoice” for the car. Part of the invoice made mention of a “rebuilt 350 engine”. I thought perhaps that was just a typo since during my initial conversation with the dealership, I’d inquired as to the status of the (advertised) big block engine and transmission, which I was told that all they knew about the engine was that it “appeared to have been rebuilt”, and that they thought the transmission was a “Turbo 350.”

So I emailed them back stating that everything looked good save for the part about the “rebuilt 350 engine.”

That’s when things took a turn for the worse.

The salesman responded with an adamant proclamation that he told me the engine was NOT the one shown in the ad, but instead had been replaced with what they thought was a “rebuilt 350.” The only thing I can come up with is the dealer must have been suffering from a case of “selective amnesia”, because he most certainly did NOT mention that the car had a small block engine in it when we negotiated the price! Had he mentioned that to me during the negotiation, I would NOT have paid as much as I did for the car.

At this point, I was on the verge of cancelling the entire deal. However, after some consideration, I decided that it might be a poor decision to nix the deal over the issue. After all, the car was supposed to be “100{e8a31ad70eb76b9d1736af28c4c10c5ce60babf18dd7728d2fa05ac44ba5f2cd} rust-free”, remember?

There’s a lot more I’d like to say about this transaction at this point, but sometimes it’s just best to let sleeping dogs lay.

The big block that the car was advertised with was indeed gone, and in its place was what they referred to as a “rebuilt 350″…only problem is, it wasn’t even a 350, and it certainly was NOT rebuilt! When the numbers on the engine were checked out, it turned out to be a 305 from a 1978 Camaro! It had an early Carter pattern intake manifold on it with a junk Edelbrock AFB carb (several corners of the carb had been broken completely off, I’m guessing by an engine hoist chain), and when I removed the valve covers, I found the heads were big chamber “882” castings from an early `70’s 350, not to mention a significant amount of burnt oil sludge. So much for being “rebuilt.”

I’ll bet that 305 really ran like a champ. Oh…the “Turbo 350” transmission part was correct. Only one problem though…the case was cracked 1/2 way around the entire bellhousing.

This deal was just getting better and better by the minute. At least the VIN tag and Trim Tag checked out legit; it was in fact a real 138 code Super Sport car. Figuring I’d once again just learned one of life’s little lessons, I shoved the car into the garage and began to assess what I had to work with.

The front end was sans any major rust holes, but the drivers side fender was more than a little wavy. The passenger side fender appeared good. Both inner fenders were hacked, as was the radiator core support and the firewall for add-on air conditioning. (this car did come from the southwest area, and add-on A/C was a common addition to cars from that area)

So right off the bat, I’ve got a garbage small block, a garbage transmission, a garbage carburetor, and all of the front end sheet metal is going to need replaced.

How quaint.

Time to move rearward and see what’s hiding in the rest of the car.

Gutting the interior: More evidence that there are people in this world who should NEVER be allowed to work on a car.

Boy, was I in for a treat when I gutted the interior!

What I found underneath the carpet was a first for me. Apparently, somewhere along this poor car’s lifetime, someone thought it would be a good idea to lay down multiple sheets of roofing tar paper, and if that wasn’t enough, they also thought it’d be a good idea to glue the tarpaper down with roofing tar!

Talk about dreading a task. But, what had to be done, had to be done, so I dove in, struggling to peel up the multiple layers of glued-down roofing tar paper. Talk about slow progress! Thank God I have a compassionate girlfriend…after seeing me out there struggling with the paper, she came out and volunteered her help. It took the two of us two solid days to get all that tar paper scraped up and to get the floors back down to their original finish.

This was the final part of the horrifying mess I found hiding underneath the carpet. Most of the tar paper had been scraped out by this point. For reference, I wound up with two FULL 35 gallon heavy-duty trash bags full of tar paper by the time we were done. This took two solid days of scraping and prying, carefully heating a small section at a time with a propane torch to help soften the tar and the tar paper so it could be scraped off.

Notice that shiny spot on the left side of the drivers footwell? That’s where someone had pop-riveted a sheet of aluminum to cover up rust holes in the floorpan. And how about that butchered shifter hole?!?

At this point, I was unsure if the remnants of the shifter hole were factory or not, and if it was a factory hole, I couldn’t tell if it was originally for a manual or an automatic transmission. The car arrived to me with an automatic brake pedal assembly installed, but subsequently decoding the trim tag revealed the car was in fact an original 4-speed bench seat car. This was further reaffirmed when I went to remove the brake pedal assembly and found it was only loosely bolted in place. Luckily I managed to find a donor section of floorpan from a `67 Olds 442 on eBay that still had an original GM transmission “hump” intact, which I grafted in.

After finally getting the engine build wrapped up, it was time to get back to spinning wrenches on the car itself.

One of the other not-so-pleasant “surprises” I was greeted with after the car arrived was some obvious signs that the car had at some point in time been hit fairly hard in the front. Notice in the pics the wrinkled passenger side front frame horn, and a stress crack on the bottom of the passenger side frame rail just behind the front lower control arm mounting points.

It was fairly obvious that the car was going to need some professional attention to straighten out the frame. I was referred to a body & frame shop by a friend, but despite almost two months of attempting just to set up an appointment for the car, I gave up on frame shop #1. Several more phone calls resulted in another recommendation, “Dick’s Paint & Body Shop” in Piqua, Ohio.

After a relatively brief conversation with the proprietor Bob Jones, I was assured the car could be quickly and (relatively) easily repaired. The car was picked up the following week, and in a mere two weeks, the repairs had been made and the car was ready to come back home.

About one week into the job, I ventured up to their shop to grab some pictures and get a first-hand report of just how extensive the frame damage really was. As the old saying goes, “it ain’t good, but it could’a been worse.”

Once the car was on the frame rack, the damage was assessed. The right front frame horn was obviously wrinkled, and the frame at the firewall body mount was also high by about 3/4″ as witnessed by the pics below. The left frame horn was also slightly out of place, being pushed back by about 1/2″. Lastly, the rear most crossmember behind the rear bumper had been seriously tweaked out of shape.

The damage indicated that at some time, either the car itself had been used to pull something with, or something had been used to pull the car–by a chain or rope that had been wrapped around the rear crossmember. Once the rear bumper was removed, it became apparent that the easiest way to fix the crossmember would be to cut it from the car, straighten it on a workbench, then weld it back in place.

The required repairs weren’t exactly “cheap”, but they were done right, and they also allowed me to retain the cars original frame.

The front floor pans and the butchered shifter hole shown on the previous page have been repaired as well.

The rusted section of the drivers front footwell was carefully cut out and used as a template to cut a graft from a new front floor pan repair section. The edges were carefully trimmed in and the floor patch was butt-welded in place rather than taking the easy way out and lap-welding the repair in.

The welds were fully dressed and blended in. The goal is to keep the repairs as invisible as possible.

I spent a LOT of time making sure the grafted-in trans tunnel repair section and shifter hump were correctly positioned.

As was common with many southwestern cars (remember, this car came from Arizona), this car had at some point been equipped with aftermarket add-on air conditioning. As such, there were several additional holes in the firewall that needed to be repaired.

A couple of hours were spent trimming out the appropriately-sized patch plugs, which were then mig welded in place. Again, these repairs are only roughed-in at this point. All of these repairs will be fully blended in during the body-off process.

Notice anything missing from the top of the frame rail here? Here’s a hint—remember, this is a 4-speed car.

Yep…someone scarfed the clutch cross-shaft pivot bracket off of the frame. Luckily I managed to find a reproduction replacement which will be installed soon.

As I’m sure you’ve noticed by now, the 496 is sitting in place along with an empty Muncie 4-speed transmission case for mock-up purposes. First, I needed to make sure my shifter hole repair was located properly, which it is. I also needed the engine in place so I could make sure the new clutch cross-shaft pivot bracket gets welded back in the correct location as well. Lastly, I needed to make sure the headers were going to fit without any modifications before I send them out for ceramic coating.

So here’s what’s on the “to do” list next;

Once the clutch bracket is welded back on and the header fitment has been verified, the body is coming off the frame. The frame will be stripped and sent out for powdercoat along with the front upper & lower control arms. The rear control arms will be replaced with aftermarket units. While the frame is being done, the floor pans and firewall will be cleaned and dressed in preparation for painting.

Once the frame is done, it will be assembled with all new front steering and suspension parts (bushings, ball joints, tie rods, etc.) and a rebuilt manual steering box. The 12 bolt rear end will be detailed and installed, and once the chassis is a “roller” again, the body will be re-installed using all new body mounting hardware.

Coming up next!!!… Chassis work, steering box work, floorpan work, and a sneek peek at the wheel & tire combination!

Now that the car was back from the frame shop, the real fun was about to begin; it was time for the body and the frame to come apart for the first time since the car was born over 40 years ago. Surprisingly enough, most of the body mounting bolts came out without issue, but three of the body bolt nuts did break loose in their cages; the drivers side front and two in the rear in the trunk area.

Getting the front mounting bolt free from the broken cage nut was easily resolved with a pair of C-clamp vice grip pliers. Unfortunately, the two rear bolts required some minor surgery to the trunk floor to access the broken cage nuts. It’s really only a minor inconvenience, as the access openings will be welded back in place, and once the welds are dressed and a fresh coat of trunk spatter paint is applied, the repairs will not be noticeable.

Here are the two rear body mounts that decided they didn’t want to come out. I hated to take the cut-off wheel to the car, but there was no other choice. At least these repairs will be fairly easy.

Next I began dis-assembling the chassis and suspension components so they could be cleaned and detailed for re-assembly. As the disassembly process is pretty straightforward, I didn’t bother to take any pictures of that. Below are some pictures of a few details of the cleaning and detailing process instead, as well as a few issues I ran across in the process.

Here is the 12 bolt rear end that will serve time under the car. This particular axle is a `68 dated unit which I picked up very reasonably; I searched for quite a while but was unable to locate a properly dated `67 housing, so the `68 will have to make due for now.

This particular housing is a “KJ” coded unit, which translates to a 3.55 gear equipped with a positraction differential. However, for the time being, a Richmond 4.56 gearset was installed for initial track testing purposes. The 4.56 gears will be replaced with either 3.55 or 3.73 gears soon after the initial series of track testing baselines are obtained in order to see exactly how much of a difference the steep gears really have on e.t. with an engine such as this projects 496.

As seen here, the 12 bolt housing had some surface rust issues that needed to be addressed before any detailing and/or painting could commence. A couple of hours with the sandblaster cleaned the housing up nicely.

At this point, I need to make mention of the fact that at some point in its life, this car was subject to the hands of someone who should’ve never been allowed to pick up a wrench. (the butchered shifter hole mentioned earlier should’ve been your first clue)

Somewhere along the line the car’s original 12 bolt rear end was liberated from the chassis, and in its place was a mystery 10 bolt 8.2 rear end. (I didn’t even bother checking the codes on the 10 bolt) During the disassembly process, I found the source of a mysterious “clunk” I’d heard several times earlier when the car was still a rolling chassis; whenever the rear suspension was bounced, there would be an audible clunk. Since the car was coming apart anyways I never bothered to look into what was the cause. I found out when the rear end was removed.

Whoever performed the rear end swap somehow managed to overlook the fact that the front bushing in the drivers side upper control arm was missing completely!!…even the outer shell was missing! How this gets past someone is beyond my comprehension.

As such, it came as no surprise to me that after stripping the control arms, I found the drivers side upper arm to be cracked. Since the drivers side arm is the one that’s proprietary to the 12 bolt rear end, rather than scrap it in favor of a new replacement, I decided to weld the crack.

This is an original control arm specifically used with 12 bolt rear ends.

The center casting of the 12 bolt housing is considerably larger than that of it’s 10 bolt “little brother”, and as such, requires additional clearance in this location on the drivers side upper control arm.

The reinforcement is factory-added.

To note: the 12 bolt arms can be used without modification on a 10 bolt rear end, but an unmodified original 10 bolt control arm will interfere with a 12 bolt housing.

Since the trip to the dyno proved that the 496 will provide plenty of “GO”, the next thing on the list to address was what would provide the “WHOA”.

Lucky for me, a previous owner had the courtesy to install a set of factory 11″ disc brakes on the front, which will provide a dramatic improvement over the OE drum front brakes. Speaking of drum brakes…while rear disc conversions are all the rage these days, I chose something a little more practical and affordable, MP Brakes 11″ factory drum conversion. This kit consists of all new backing plates and brake hardware, and it comes completely assembled save for emergency brake cables.

Figuring early on that I wanted to replace the cars existing (and wasted) power steering setup with a manual one, I located an original, and as such, well-worn manual steering box for the car on a certain popular internet auction site. Rather than tackle the restoration of the steering box myself, I sent the box out to a member of the Supercar Registry, Mr. Casey Marks. Sometimes you’re better off knowing when to tackle a job yourself or when to farm it out. This was a time to farm it out.

As you can see below, Casey’s work speaks for itself.

As soon as the frame was disassembled, it was sent out to Aesthetic Finishers in Troy, Ohio, for powdercoating.

Why powdercoat instead of paint? Several reasons, not the least of which is the fact that this car is going to get driven, and powdercoat will hold up much longer than paint will.

Combine that with the fact that what Aesthetic Finishers charges to completely strip and powdercoat a frame is paltry in comparison to the time and trouble it saved me, it was money well-spent.

The quality and detail speak for themselves. The color match to OE is very good as well.

Here is the frame after powdercoating. I am extremely pleased with the job Aesthetic Finishers did. As you can see, some of the re-assembly has already begun, but there is still a long ways to go, and a lot of parts left to be bought.

It sure is nice to see parts finally going together at this point instead of coming apart. The rear end is now in place, waiting for the coil springs to be refinished and shocks & lower shock mounts to arrive to complete the installation.

One of the most important aspects of a build like this is the wheels & tires. Bear in mind that I’m building this car with a “Day 2” lean; as such, period-correct rolling stock was essential.

While there was an abundance of aftermarket tires & wheels available back in the day that would suit the car quite well for this build, I instead chose something a bit more “unconventional” for wheels–plain-jane stamped steel jobs: 15X7 units on the rear wrapped with a pair of original (read: “not reproduction”) Goodyear Polyglas GT L60X15 tires, and a pair of 15X6 steelies for the front which will be wrapped in F70X15 Polyglas tires.

Once the frame reassembly was complete, the cleaning and detailing of the floorpans commenced.

As 40 years of blecth and goo were unceremoniously removed from the floorpans, some previously hidden issues became apparent.

Some fairly serious rust issues on the rear wheelhouses and the surrounding areas of the trunk floor had been cleverly hidden under a layer of fiberglass mat and undercoating. (where have we heard that before??)

Once the wheelhouse and trunk floor repairs had been made, the bottom of the floor pans were primed, sanded and painted with semi-gloss black paint similar in appearance to the factory hue. Again, I couldn’t get a decent picture of the painted floor, so…

Once the floorpan cosmetics were completed, the body and frame were once again united. Since I wound up doing this job by myself, I wasn’t able to take any photos of the process, but suffice it to say they went back together without a hitch.

With the body and frame reassembled, I decided now would be a good time to get the engine and transmission installed. But…before I could install the engine, there were a few issues that had to be taken care of first.

If you’ve taken the time to read about the engine build for the car, you’ll know that there were some oil control issues present when the engine was ran on the dyno. In a nutshell, the stock GM oil pan wasn’t able to provide adequate oil control as the engine surpassed approximately 5500 rpm. To remedy this issue, I contacted Chris Straub to purchase a STEF’S custom oil pan for the car. After discussing the issue with Chris, we both agreed that one of STEF’S steel 6-quart pans with a built-in windage scraper should solve the oil control issues. While an aluminum oil pan was a possible option, I decided to go with the steel pan since this car will see a considerable amount of road time and I didn’t want the worries that can come with an aluminum oil pan, such as possible damage from road hazards, possible cracking issues (not at all uncommon with aluminum pans), etc.

About 4 weeks after my order was placed, the oil pan arrived. To say I was pleased with its construction would be quite an understatement. Not only was it made of 16 gauge steel (a lot thicker than the OE pan), but the welds were absolutely beautiful. The biggest pleasant surprise came when I went to install the pan on the engine. The fit was absolutely perfect…and I mean absolutely perfect. Every bolt threaded in by hand, and there was absolutely no warp present whatsoever. If there was one hitch in the installation, it was the oil pump pick-up tube that was supplied with the pan. While it too is a work of art, the tubing size is slightly over-size compared to a conventional pick-up tube, which requires the pick-up tube bore on the oil pump housing to be enlarged slightly to allow installation. Please note that this is an intended deviation by the manufacturer and not a mistake or an oversight, and while it may be an inconvenience when it comes time to assemble the oil pump and tube, it’s a minor one. (*Note* STEF’S does offer a pre-assembled pump & pickup, I just opted to do the job myself)

With the oil pan issue resolved, it was time to choose a flywheel and clutch system to transfer the power aft. Since a scattershield wasn’t originally going to be an option for the car, the need for the highest-quality clutch components was paramount. As such, I chose a HAYS billet steel flywheel (part number 10-235) and a RAM 11″ “Powergrip” clutch kit (part number 98762). The Powergrip clutch offers an advertised 30{e8a31ad70eb76b9d1736af28c4c10c5ce60babf18dd7728d2fa05ac44ba5f2cd} improvement in clamping power over an OE clutch.

The natural choice for transmission to back this all up is a Muncie. However, even the highly revered M22 “rock crusher” wouldn’t likely be long for this world in its stock form behind the 496, so a “factory” based box was out. Aside from that, I wanted to utilize the steeper gearing of an M20 based box, so that excluded the M21 and M22 from my options list. After discussing the matter with my transmission builder, I decided to build an M20 based box using an Autogear “Supercase” and their cast iron mid-plate. The major internals are all original GM components.

For shifting duties, an original GM shifter was obviously not going to cut it. As luck would have it, I managed to score a brand-new Hurst Competition Plus shifter AND the appropriate installation kit for my exact application from a certain popular internet auction site for roughly 1/2 the cost of new.

Sweet.

Those who’ve been following this build may notice this is where the original build thread ended on my old website. When the original hosting site went under I had to have the site transferred to a new hosting site. Unfortunately I didn’t have the technical knowledge to know how to edit and update the new site, so it essentially remained in limbo until now. I’m now able to edit and uptate things on this new site, so without further ado, let’s get back to the build.

Skipping ahead a bit;

I managed to get the car assembled and running in 2008. The mechanicals were basically sorted out, but (as has often the case with many of my projects) the car remained “aesthetically challenged.” I struck a deal in 2010 with a body & paint man to at least get the rust and other structural issues resolved on the car so it would be ready for paint *eventually*. As the body work was nearing completion, circumstances evolved that necessitated getting the car finished a.s.a.p., so I struck another deal with the body guy to finish the car out and get it into paint.

Rather than bore you with a lot of frivolous commentary, I’m just going to post the progress pics of the body work & paint below.

More coming soon!