Preface:

I have been working on this project for almost 6 years now. I had intended on having it wrapped up in 2012, but an illness in the family at the time took precedence and forced a significant change in my plans.

As such, while I had already obtained all of the parts and everything was machined and ready to assemble, due to my time constraints I asked my friend Gregg Montgomery (Son of the legendary “Ohio” George Montgomery) if he would help me out by assembling the longblock. Thankfully he obliged, and I was able to keep the project moving forward. I finished the peripherals and had the engine ready to dyno in November of 2012, but due to a number of unforeseen circumstances I wasn’t able to get dyno time scheduled until March of 2013.

This project was dyno’ed at the facilities of “Kammer&Kammer” racing in Huber Heights, Ohio.

Given the above, please note that I wasn’t able to stay on top of taking the pictures like I wanted to, so the photographic content is lacking somewhat. I was also unable to get any useable video of this.

With that said…meet project Torque Monster;

After so many builds that were focused on high horsepower, I wanted to take a swing at building a stump-puller. As it just so happened, my trusty `95 Suburban daily driver was getting rather long in the tooth, so I decided to kill two birds with one stone; I would build said torque monster, and I would use the Suburban as the test bed.

The foundation of the build is a 1997 vintage 7.4 block which originally resided in a Suburban. I picked the block up from Bob Kammer after he had line bored it to repair the damage from a spun main bearing and bored & honed the block with torque plates.

Here’s the block at George’s in the clean tank getting washed up for assembly.

The crankshaft is a Callies “Compstar” unit featuring a 4.25″ stroke (1/4″ over stock 454) and center counterweights which enable the rotating assembly to be internally balanced. Here it is on the balancer.

The rods are Scat forged I beam units measuring 6.385″ long. The pistons are SRP forged flat tops which use a 1/16″ 1/16″ 3/16″ ring pack. The rings are a custom set from Total Seal.

The cam is a Crane hydraulic roller unit featuring 204°/214° duration @ .050″, 260°/270° advertised duration, .486″ lift on the intake and .512″ lift on the exhaust and a 112° lobe separation angle. The lifters, retainers and spider are all new GM components as is the timing set.

With the machine work completed and the parts washed up, it was time for assembly.

Gregg then degreed the cam.

The cylinder heads are a set of factory GM iron oval port open chamber units. I had cylinder head guru Dave Layer (RIP) work his magic on them, fitting them with 2.25″/1.88″ stainless steel valves, and a basic street port job.

With the 119 c.c. chambers in the heads, the final compression ratio came out to exactly 8.5-1. This thing should be able to run on just about any sort of pump swill out there.

Once the heads were assembled, Gregg bolted them down and installed the valve train.

I took over the build at this point. I installed a standard volume/pressure oil pump, a hardened one piece oil pump drive shaft, and the bottom end was capped off with a Milodon 8 quart oil pan and a Fel-Pro one piece gasket.

A Powerbond 8″ SFI balancer was installed next. This is a very high quality unit which features engraved timing marks. (please note: this is not a Chinese balancer)

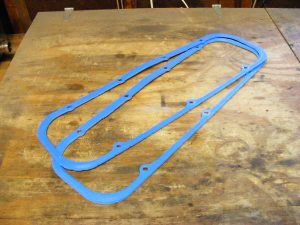

Next up was a pair of GM Performance Parts cast aluminum valve covers, and a set of Fel-Pro valve cover gaskets.

For an intake manifold, I was forced to make a compromise I was VERY uncomfortable making: I needed a dual plane intake manifold which featured tapped water outlets at the rear of the manifold. This was necessary in order to accommodate the heater hose routing when the engine goes into the Suburban. As it turns out, there is only one manifold available that suited my needs, and it’s one I do not care to even mention the name of.

The manifold was bolted down using a set of FelPro intake gaskets.

Wrapping up the final peripherals of the build were a GM Performance Parts HEI distributor, Moroso plug wires, NGK spark plugs, and a Stewart heavy duty water pump. Gibson stainless steel 1 3/4″ shorty headers were used with a 3″ cross-over pipe which fed into a Flowmaster dual 3″ in to 4″ outlet y-pipe, then into a Flowmaster 4″ truck muffler. Here’s the headers & Y-pipe being mocked up before the dyno session.

This essentially wraps up the basics of the build. Here’s the engine on the dyno just before the last two pulls were made.

Testing commenced with 5 gallons of Valero 92 octane in the fuel cell, and a restored Holley LIST 4053 `69 Z28 carburetor I had in inventory. The engine was pre-oiled, fuel pressure was set to 6 psi, and the engine was brought to life. Timing was set to a conservative 32° total, and once the engine reached operating temp, a very soft pull was made from 2100-4000 rpm. The engine responded with 460 lb.ft @ 2100 rpm, peak torque of 535 lb.ft at 3300 rpm, and 385 HP @ 4000 rpm.

Before I go any further, note that my goals with this build were 550+ lb.ft of torque as early as possible, and anything over 375 HP was icing on the cake. The first pull got me past the HP goal and within 15 lb.ft of my torque goal.

The 2nd pull was a repeat of the first just to establish consistency. This time it responded with 499 lb.ft @ 2200 rpm, peak torque of 535 lb.ft at 3300 rpm, and 388 HP @ 4000. I’d call that consistent.

The third pull saw a bump to 5000 rpm. This time it made 513 lb.ft @ 2300 rpm, peak torque of 534 lb.ft @ 3300, and 410 HP @ 4700 rpm. HP @ 5000 only fell to 408, so there was very little drop-off above peak HP.

Pull #4 saw a bump to 36° total timing. The engine did not like the extra timing in the lower ranges as torque fell to 503 lb.ft @ 2300, peak torque of 530 @ 3300, but peak HP bumped to 410 @ 4600 and 5000 rpm.

For the 5th pull, the timing was brought back to 32°, and I removed the supplied medium-weight advance springs from the GM Performance Parts HEI and installed a set of heavy springs from a Moroso HEI advance curve kit. The engine definitely liked the slower curve as torque now hit 512 @ 2300, peak stayed approximately the same at 532 @ 3300, and peak HP climbed to 415 @ 5000 rpm.

Pull #6 was a bit of an eye-opener for me. Until this point the engine had been running a good used set of stock GM stamped steel rocker arms. I removed them and installed a new set of Crane Nitro Carb stamped steel rockers. The Crane units are far more accurate than the OEM units as far as ratio goes, but unfortunately I neglected to note how far Gregg had ran the adjuster nuts down to past zero lash. I “guesstimated” and set them at 1/2 turn pre-load and the next pull revealed torque had fallen to 504 @ 2300, peak torque was now 528 at 3200, and horsepower was down to 406 @ 4700. Obviously there was no likely chance that the better rockers were causing a power loss, so I attributed it to not having the rockers set the same as before. A subsequent test more or less confirmed that suspicion.

The 7th pull was a repeat of #6 save for a slight change in coolant temp, and saw 511 lb.ft @ 2300, peak torque of 532 lb.ft @ 3300, and peak HP of 405 @ 4900 rpm.

The 8th pull saw another slight bump in oil & coolant temps, and resulted in 512 lb.ft @ 2400, peak torque of 531 @ 3300, and peak HP of 404 @ 4700. We confirmed that this engine was not very sensitive to coolant or oil temps at this point.

The 9th pull was another eye-opener–not for me, but for a couple of other people involved in the test who didn’t think the change I suggested would result in any measurable differences in power; up until this point, all pulls had been made at an acceleration rate of 600 rpm per second. What this means is that the dyno will only allow the engine to accelerate at 600 rpm per second–no faster, no slower. I suggested we slow it down to 300 rpm per second, and the results were interesting. I can offer my personal theories as to why, but that would mean a lot more typing, so lest I ramble…

Torque took a jump to 516 lb.ft @ 2400, but peak torque took a nice move up to 545 lb.ft @ 3100, and HP climbed to 413 @ 4600.

The 10th pull saw a reduction in timing down to 30°, strictly to verify we had found the “sweet spot” @ 32°. Torque hit 516 @ 2400 rpm, peak torque was 542 lb.ft @ 3200, and peak HP was 412 @ 4700.

The 11th pull again saw a bump in oil and coolant temps. Torque was 505 @ 2400, peak torque was 535 @ 3100, and peak HP was 408 @ 4700. Again, we confirmed that the engine was not very sensitive to oil or coolant temp variances.

For the 12th pull, the 4053 Holley was removed. In it’s place went a 750 cfm Rochester Quadrajet I’ve been working on for a while. While I had live tested it on my “mule” engine, it was technically an unknown as I’d never tested it under any sort of load. To note, I also readjusted the rocker arms to 1/4 turn pre-load at this time which does introduce another variable, but either way the results were more than favorable.

When the throttle was opened, it was noted while observing the Innovative WB O2 sensor that the engine went VERY rich below 3000 rpm, showing A/F ratio dipping into the high 10’s. This indicated that the secondary air doors on the Quadrajet were opening too soon, but we went ahead and made the pull anyways. Torque hit 512 lb.ft @ 2300, peak torque jumped to 546 lb.ft @ 3200, and peak HP rose to 419 @ 4700!

The QJet done put a whoopin’ on that tried & true 780 Holley!

For the “LUCKY” 13th pull, I re-adjusted the air door tension another 1/4 turn tighter. That’s it, no other changes.

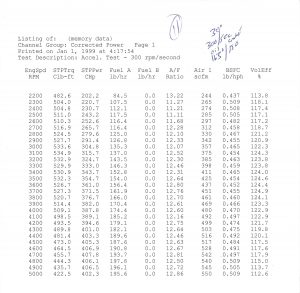

Here’s the actual 13th pull dyno sheet.

511 lb.ft @ 2400, peak torque of 555 lb.ft @ 3300, and 419 HP @ 4700 rpm.

The Innovative was still showing a rich spike as the secondaries were opening, so there was even more left to be had with a little more tuning, but time was running out so I decided to call it a day.

Not too shabby for such an incredibly mild build, if I do say so myself. I wanted 550+ lb.ft as low as I could get it, and I got it. I wound up exceeding my horsepower goals by nearly 50 horsepower, which may actually be an issue since this engine will be converted to fuel injection when it goes into the Suburban, and there’s some question as to whether or not the intended system will be able to keep up with that much HP up top. This is why I tested the engine with a carburetor–to give the computer tuner a solid accurate baseline from which to tune.

So that’s a wrap for now on this build. Unfortunately, I still haven’t gotten the engine into the truck yet as I haven’t been able to set aside enough time to take the truck out of commission to get the swap done. I do plan to do a before/after chassis dyno session with the old engine before the swap to further quantify the results. Testing will be ongoing, and I’ll follow up here with the results.

Thanks for reading.